The Computational Scrawl Session 2

Day 7 ~ Code Societies ~ Winter 2019 ~ Taught by Allison Parrish

This two-part workshop examines the physical gesture and material artifacts of the act of writing, as seen through the lens of computation and digital media. Taking contemporary and historical practices in asemic poetry, experimental typography and automatic writing as inspiration, participants will use the Python programming language to prototype speculative writing technologies that challenge conventional reading practices and notions of sense-making.

Day 7 of Code Societies was led by poet and programmer Allison Parrish. This was the second of two sessions entitled the Computational Scrawl, a workshop where we engaged with the act of writing, its materiality and how it relates to computation and digital media.

In the first session, we focused on the form of a text. For this second session, we focused on the act of asemic writing. In other words, we began to consider the visual operation of the letter and how they come to represent language. We are, of course, exploring this through computation.

The prompt that Allison used to begin this class was “What is writing?”. The etymology of the word English word “write” goes back to the words “scratch”, “tear”, and “carve”. Early forms of writing involve carving marks into or the scratching of malleable surfaces like clay or wax. It is interesting to make a distinction between automatic writing and asemic writing. The former is still bound to text as representative of language. While it might not be legible it is still attempting to have itself read. The latter can be compared to abstract painting. It is its own representation of language if it is representative of any language at all. It can evoke the appearance of writing but puts much more value of the visual qualities of writing in order to perhaps create a system that can be “read” by someone regardless of the languages they speak.

Throughout this session I kept wondering, but what is the purpose of asemic writing? Who is it for? Why make it? We discussed examples of asemic texts like the Voynich manuscript and Xu Bing’s “Book from the Sky”. There are people who are still trying to “decode” the Voynich manuscript which to me highlights a possible reason to make asemic writing at all: to avoid analyzation and instead to make the processing of the text an experience which can only be personal. Inspired by the Voynich manuscript, Luigi Serafini made “Codex Seraphinianus”, a large book of asemic writing and drawings which he says have no inherent meaning and are meant to incite the reader’s imagination.

During the second half of class, Allison led us through a tutorial in which we used a Python library called flat to draw shapes with code. In addition to learning flat we also used the random functions from Numpy and bezmerizing a library written by Allison that allows you to make to make various kinds of asemic writing using Bézier curves.

We started by first making shapes with the flat library. Using functions like shape(), fill() and stroke() we were able to generate some basic shapes of varying sizes and colors.

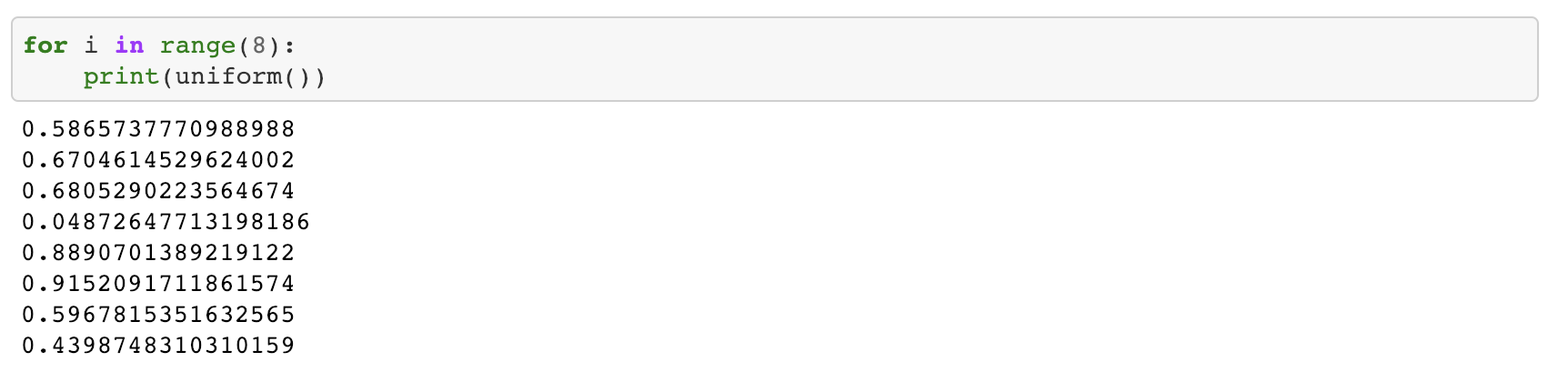

We then learned how to use random number generators with the numpy library. We tried the uniform() function first. This function will return a number between 0 and 1 in “uniform distribution.” In other words every value will have the same chance of being returned.

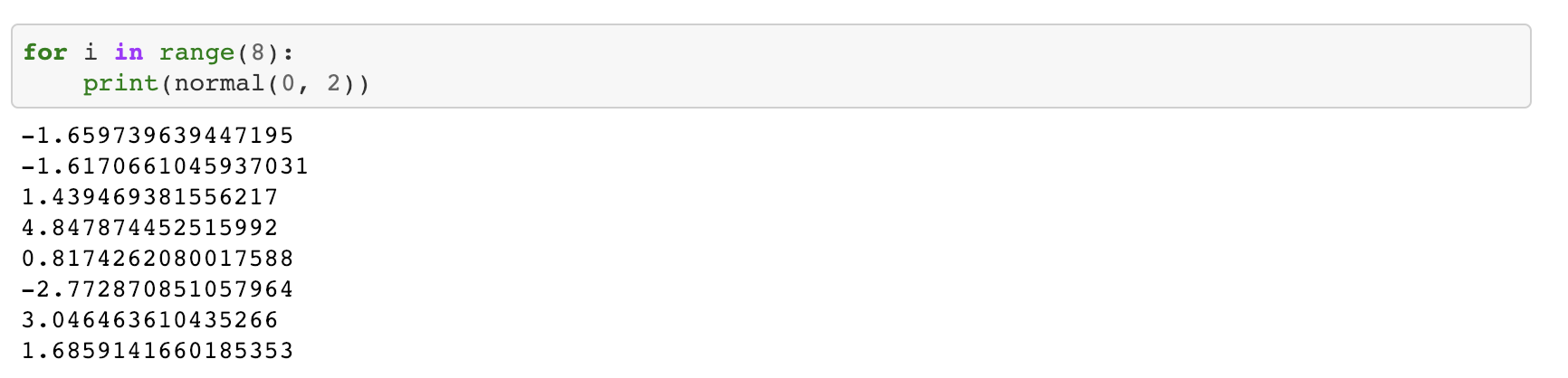

Next we tried the normal() function for generating random numbers. This function does something a little different - it returns values that will cluster around a given number. The normal() function takes two arguments: the first is the “center”, in other words the number that the values should cluster around and the second is the standard deviation.

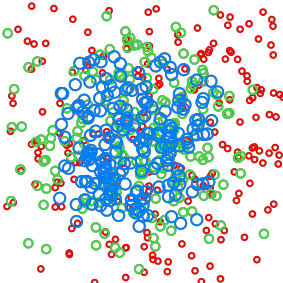

Now we were able to visualize these random number distributions by using them with the shapes we created earlier.

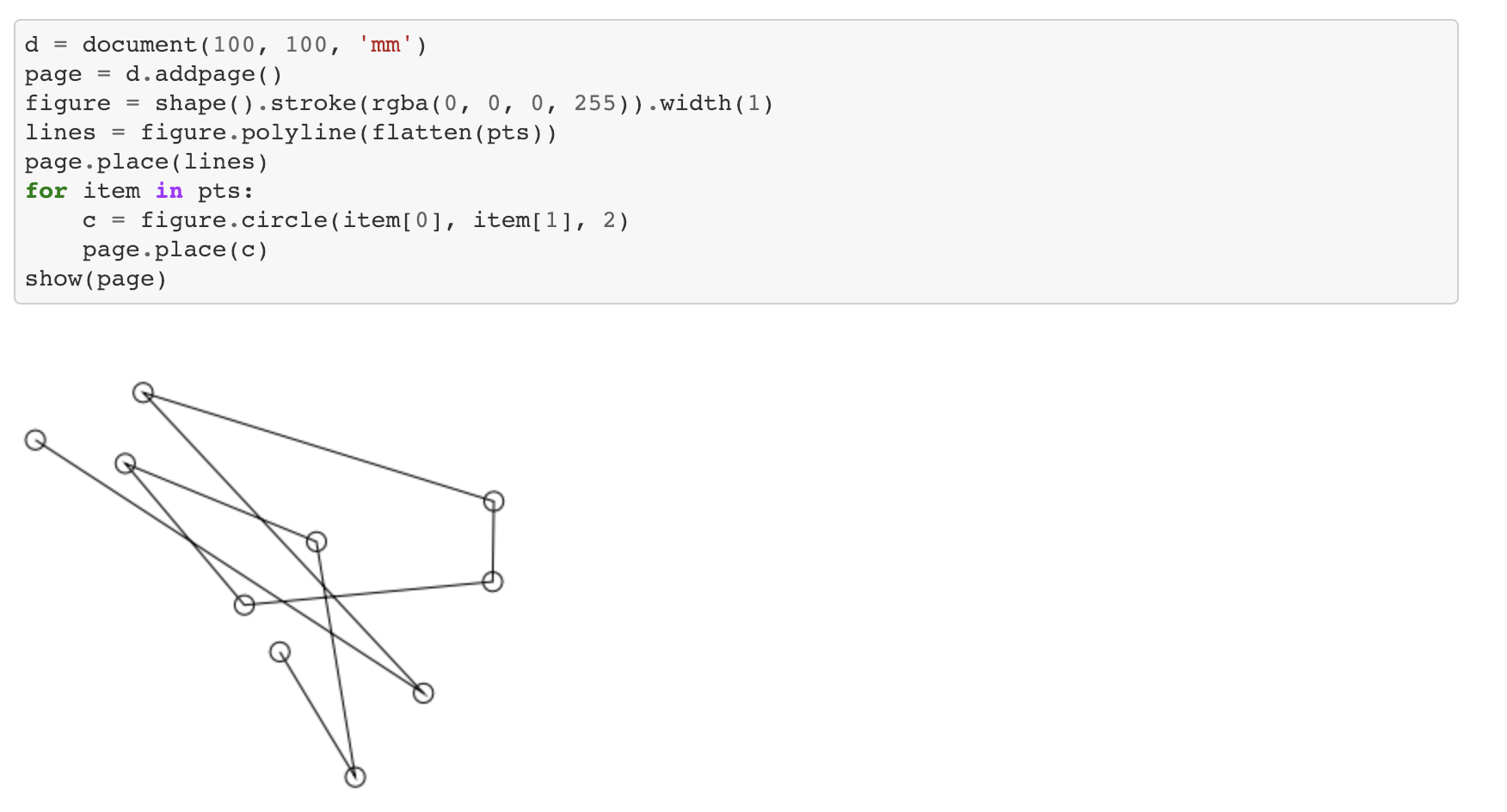

In order to start to make our shapes and the placement of them look more like writing we had learn how to create polylines. Creating polylines requires denoting a series of points on a plane and then connecting them. The flat library has a polyline() function so by using a random number generator to mark a series of points we could then pass those points into the polyline() function to create an outline of shape.

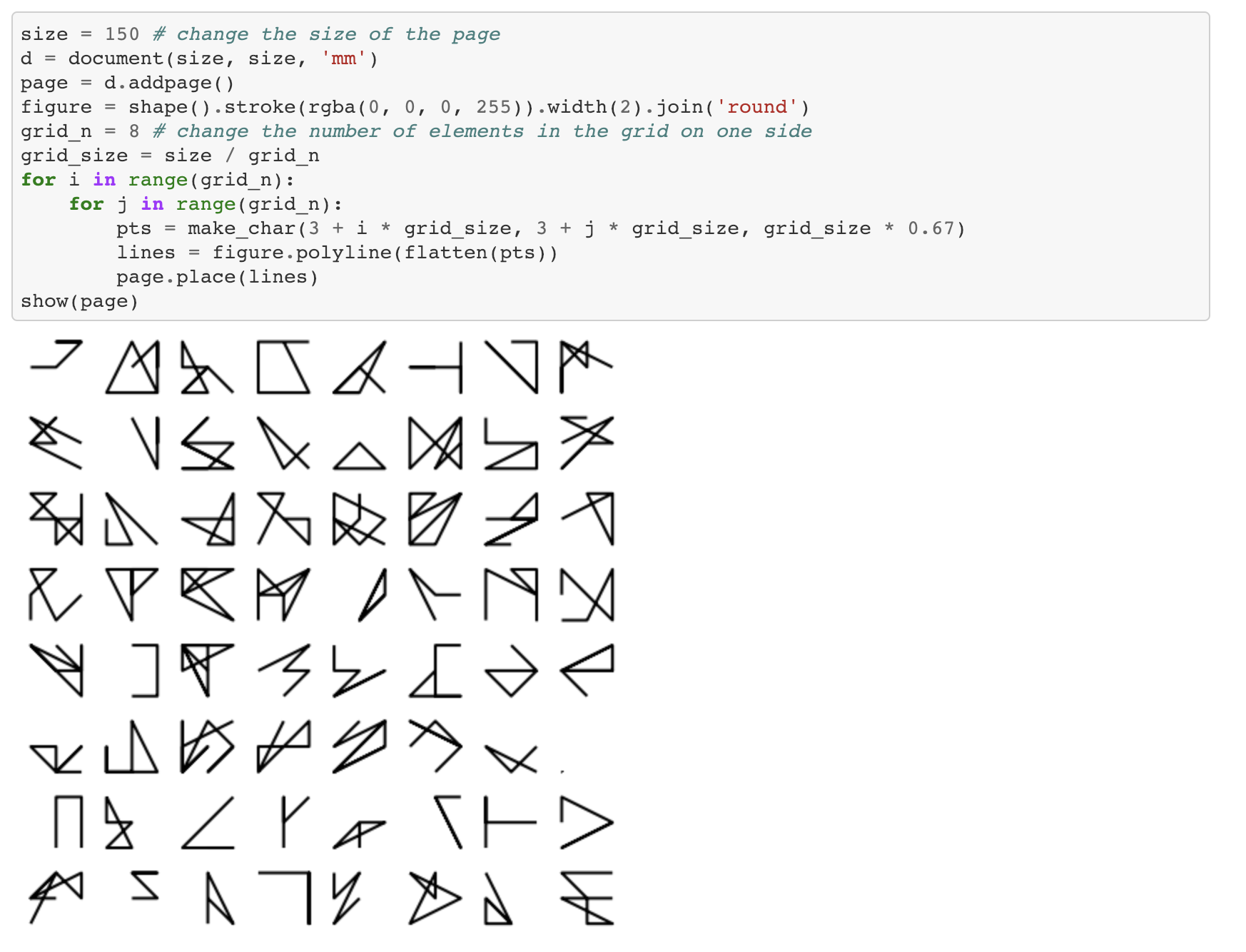

Eventually we were able to put these outlined shapes onto a grid - the asemic writing is starting to come together here!

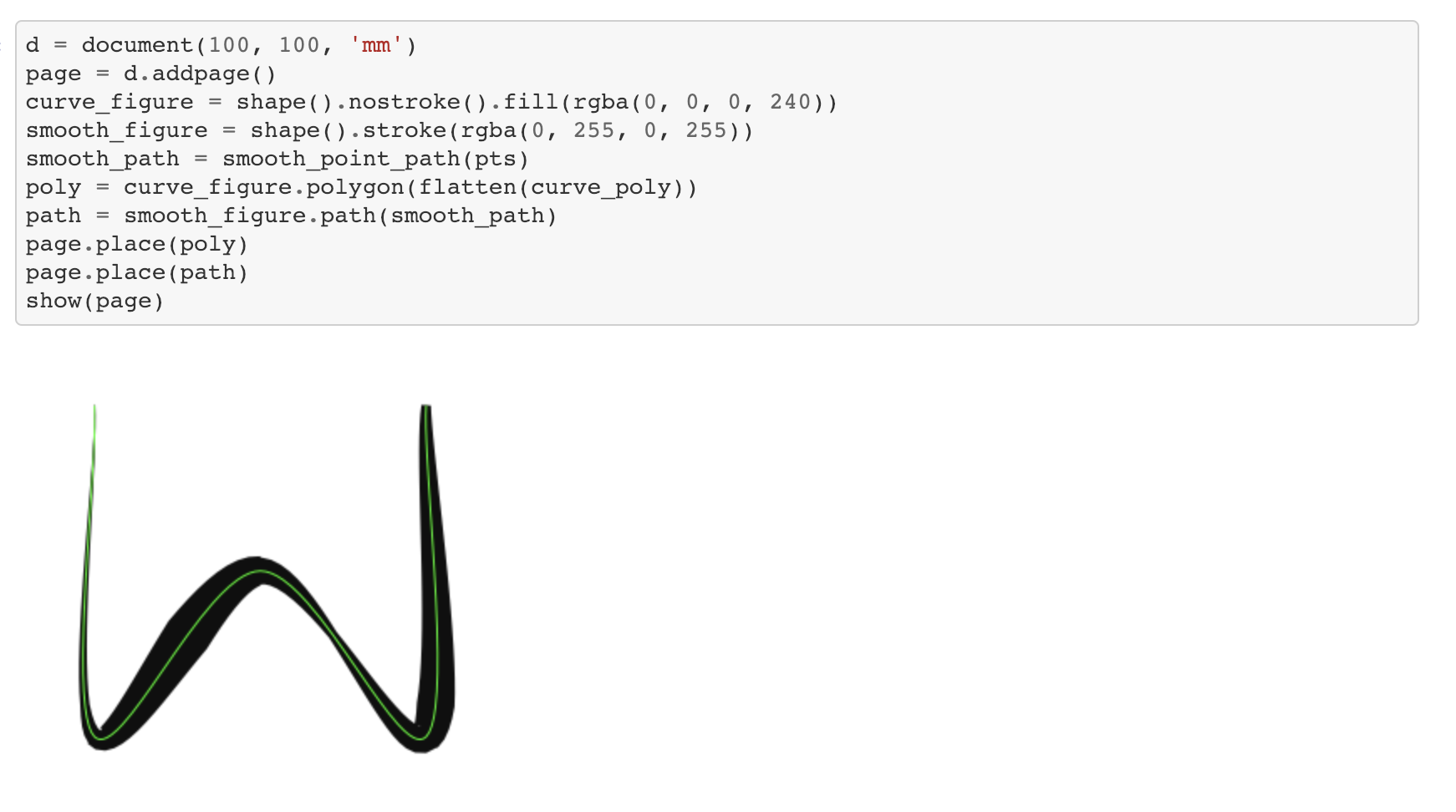

Finally we got to try Allison’s bezmerizing library which allows you to add weight to particular parts of a line. This allowed the shapes to have more character.

It seems like the possibilities for what computational asemic writing can be are endless. I’m wondering how important random number functions are in these exercises. Is a random number function a sort of equivalent to a subconscious/unconscious choice when making marks on a page? There is a constant push and pull between trying to make something look a certain way but also not intentionally creating something representational. Asemic writing seems to sit right in between these two. Whether it is asemic or automatic or completely intentional like the writing in this blog post I am very much looking forward to exploring the act of writing through computational means!

by emma @doodybrains rae norton