BeginningCodersBootcamp

Day 1: Graphics, variables & functions

Learning outcomes

- Create and run openFrameworks projects

- Introduce basic C++ syntax

- Use openFrameworks graphics functions (

ofDrawLine,ofDrawCircleetc.) in thedrawloop - Understand the painter’s algorithm

- Declare and assign primitive variables (

int,float) - Use variables to reduce redundancy

- Declare and define functions

- Generalize a function with parameters

Lecture

New project layout

First, we create a blank openFrameworks project. The following files are created for us.

main.cpp— we usually don’t need to change this file; however, we can change the dimensions of the window here.ofApp.cpp— this is the main file you’ll edit, where most of your code will go.ofApp.h— we can add variables (more on those later) to this file, but we won’t need it much for now.

Open up the ofApp.cpp file. There’s a special function within this file called draw. It looks like this:

void ofApp::draw(){

}

Functions are a way to organize code in C++. openFrameworks has lots of functions that will help us create graphical programs. The draw function is where all of the code that draws to the screen will go. If we place code between the { and }, it will be executed as part of the draw function.

Calling functions

There are two types of functions that openFrameworks provides:

- Functions you put code inside (like

draw). - Functions you call.

What does it mean to call a function? There are certain functions that openFrameworks has already written for us — these contain code which does useful things we might want to take advantage of. For example, there’s a function for drawing lines named ofDrawLine. When we use the function in our code, we say we are calling the function. It’s like we’re calling up this function on the phone and saying, “Hey, can you draw us a line?” We can also think of the function as a magical spell. By calling out the name of the function, we’re invoking the spell!

Here’s an example of how to call the ofDrawLine function inside of our draw function:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofDrawLine(0, 100, 500, 100);

}

Let’s take a look at the syntax:

ofDrawLine— this is the name of the function; it tells C++ which function we want to invoke.(0, 0, 1024, 768)— these are the parameters of our function call; they tell the function specifics about how it should be invoked. (When we call our function up on the phone, we can give it some extra instructions.) In this case, we’re giving theofDrawLinefunction information about the line we want to draw. The syntax is important here: our parameters must be surrounded by(and)and separated by,.- And lastly, the

;at the end — this is an important syntactic detail which is easy to forget. Most lines that we’ll write in C++ end in a;. If we forget to add it, you’ll get an error.

If we run the program with our function call, we should see a line drawn to the screen. Next, let’s go into detail about the parameters we’re passing to ofDrawLine.

Basic graphics

We need to cover the following basic drawing concepts in openFrameworks:

-

The coordinate system in openFrameworks has a reversed y-axis from what we’re used to. Moving down the screen means larger y values.

TODO: illustration of coordinate plane here

-

ofDrawLine(x1, y1, x2, y2)can be used to draw a line from starting point (x1, y1) to ending point (x2, y2).

For example, ofDrawLine(0, 100, 500, 100) draws a line from the point (0, 100) to the point (500, 100).

Exercise 1: Draw a diagonal line

Draw a line from the top-left corner of the window to the bottom-right corner right corner. Remember that if we want to get the width and height of the window, we can take a look inside of main.cpp.

TODO: illustration of finished exercise

Solution

Modify the draw function in ofApp.cpp:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofDrawLine(0, 0, 1024, 768);

}

What if we want to add some padding to the line, so it doesn’t go all the way to the corner? For example, we want a padding of 10 pixels from the top, bottom, left, and right:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofDrawLine(10, 10, 1024 - 10, 768 - 10);

}

Important: we can put math, like 1024 - 10, inside our call to ofDrawLine.

Comments

Comments (lines beginning with //) are an important tool for “writing a letter to yourself in code.” Example:

void ofApp::draw() {

// The following code draws a line!

ofDrawLine(10, 10, 1024 - 20, 768 - 20);

}

Setting the background color

ofBackground(red, green, blue) can be used to set the background color. The values of red, green, and blue must be numbers in the range of 0 – 255, where 0 represents “no color at all” and 255 represents “a maximum amount of that color”. Example:

void ofApp::draw() {

// full red and blue with no green makes purple

ofBackground(255, 0, 255);

}

The call to ofBackground must come before ofDrawLine:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(255, 0, 255);

ofDrawLine(10, 10, 1024 - 20, 768 - 20);

}

If the lines are switched, then the call to ofBackground overwrites the line that comes before it:

void ofApp::draw() {

// This renders a blank screen with no line

ofDrawLine(10, 10, 1024 - 20, 768 - 20);

ofBackground(255, 0, 255);

}

Painter’s algorithm

This introduces two important concepts:

- Lines of code are executed in a precise order, starting with the first line of a function and continuing down.

- The painter’s algorithm. openFrameworks graphics calls are like commands that you would give to a painter (“first paint the background purple, next paint a line”). If you command the painter to fill in a background as the last step in a list of instructions, it covers up what is below it.

More drawing primitives

Finally, we look at two more primitive drawing functions: ofDrawCircle(x, y, radius) and ofDrawRectangle(x, y, width, height). Examples:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(255, 0, 255);

// A circle at position (50, 40) with radius 20:

ofDrawCircle(50, 40, 20);

// A rectangle with top left corner at (100, 200),

// width of 50 and height of 30:

ofDrawRectangle(100, 200, 50, 30);

}

If we want to change the thickness of lines, we can call ofSetLineWidth:

void ofApp::draw() {

// draws a line with a thickness of 5 pixels

ofSetLineWidth(5);

ofDrawLine(10, 10, 1024 - 10, 768 - 10);

}

Exercise 2: Draw your name

Using openFrameworks primitives (lines, circles or rectangles), draw your name in the draw function.

Example:

Solution

Here’s the code for the image above:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// A

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// L

ofDrawLine(300, 20, 300, 200);

ofDrawLine(300, 200, 380, 200);

// E

ofDrawLine(400, 20, 400, 200);

ofDrawLine(400, 20, 480, 20);

ofDrawLine(400, 100, 480, 100);

ofDrawLine(400, 200, 480, 200);

// X

ofDrawLine(500, 20, 580, 200);

ofDrawLine(500, 200, 580, 20);

}

mouseX and mouseY

There are special built-in values in openFrameworks that allow you to access the position of the mouse. These are called mouseX and mouseY. For example, if you want to draw a circle at the position of the mouse:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofDrawCircle(mouseX, mouseY, 10);

}

If you run this program, you’ll see that the circle follows the mouse around.

This is a bit of new syntax. Rather than putting a number between the parentheses, we’re putting text: mouseX and mouseY. These are the names of variables that openFrameworks provide for us. In this case, we’re using the variable in place of numbers in the parameter list of ofDrawCircle. When the computer runs our program, it replaces mouseX and mouseY with actual numbers that correspond to the x and y position of the mouse.

Let’s discuss variables more in depth.

Variables

One of the main things a computer can do is remember information. You’ve probably heard of the term “computer memory” — this is what the computer uses to remember. Programming languages always offer a mechanism to use computer memory; in C++ this mechanism is called a variable.

A variable is like a box that we can put a piece of information inside. The information inside of the box can be recalled later. There are two core parts of each variable:

- The name that we can use to access it (in the box analogy, this is like labeling the outside of the box with a sharpie to remind yourself what the box is for).

- The type of the variable. A variable can store any time of information, but we must tell the computer what type of information is going to go inside of it. We can imagine that we have different types of boxes for storing different types of contents.

One of the simplest types of variables is one that stores a number. Here’s how we create that:

int myNumber;

The int here is the type of the variable. int stands for “integer”, and it tells the computer that we’re going to store integers in our variable. Integers are any whole numbers (including negative numbers), like 5, 2, 9999, or -345.

myNumber is the name of the variable. We can choose whatever name we want here. Anytime in the future that we want to refer to this variable, we’ll identify it using this name.

If we want to assign our variable to a value, we use the following syntax:

int myNumber;

myNumber = 5;

This stores the value 5 inside of myNumber. Think of this as putting the number 5 in a box. If we want to retrieve this number, we can use it in our program in place of where we would normally put a number. For example, to draw a line:

int myNumber;

myNumber = 5;

ofDrawLine(myNumber, 10, 100, 200);

5 will be inserted in place of myNumber when we run the program.

There are many other types of variables, and we won’t cover them all in this class. The two most important types for creative coding are int and float. A float also stores a number, but it can store a decimal number in addition to whole numbers. For example, you could use a float to store 98.6, 3.0, or 99987.3452. To declare a float:

float myNumber;

myNumber = 3.13;

ofDrawCircle(10, 10, myNumber);

The life of a variable

Variables go through the following stages of life:

-

Declaration — where a variable’s type and name are declared. For example:

float circleSize;The default value of

circleSizewill be 0. -

Assignment — where the value of a variable is set. This stores a value in the variable. For example:

circleSize = 5.5; -

Usage — where the value of a variable is recalled from memory and used in the program. For example:

ofDrawCircle(100, 100, circleSize); -

Death — variables don’t last forever; they stay alive until they reach the end of their scope. If you define a variable in a function, then its scope is the function. When the function finishes running, the variable is destroyed.

void ofApp::draw(){ float x; x = 5.5; } // variable x is not available outside of the draw // function, because it only exists within the scope // of the draw function

Note that steps 1 and 2 can be combined into a single line. This is called initialization:

float circleSize = 5.3;

Also note that a variable can be assigned multiple times:

float circleSize = 5.3;

// now store a new number inside of circleSize:

circleSize = 2.1;

Removing redundancy using variables

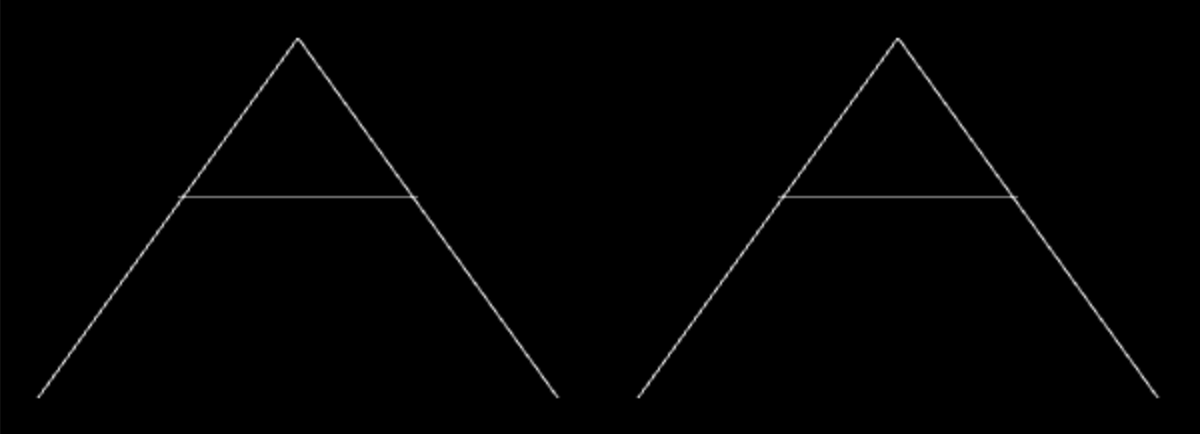

Let’s take a look back at exercise 2. We’re going to modify this example. Rather than drawing your entire name, let’s draw the first letter of your name twice:

If we want to draw the second A to the right of the first A, we need to add some offset to all of our x-coordinates:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// A

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// A again

ofDrawLine(20 + 300, 200, 150 + 300, 20);

ofDrawLine(150 + 300, 20, 280 + 300, 200);

ofDrawLine(90 + 300, 100, 210 + 300, 100);

}

I’ve shifted over the second A by 300 pixels to the right. As you can see, I’ve had to write + 300 many times in the code for my second A. Programmers hate redundancy — it makes them VERY upset. What if we wanted to adjust this 300 number by changing it to 400? We’d have to go through and replace every instance of 300 with 400, which is tedious.

Instead, let’s save this 300 value to a variable, and then use the variable in place of the number:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// A

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// A again

float offset = 300;

ofDrawLine(20 + offset, 200, 150 + offset, 20);

ofDrawLine(150 + offset, 20, 280 + offset, 200);

ofDrawLine(90 + offset, 100, 210 + offset, 100);

}

Now the value 300 only appears in one place, and is easy to change! This is a common use of variables: to reduce redundancy.

Expressions

In addition to assigning a variable to a plain ol’ number, C++ also supports mathematical expressions:

// x will evaluate to 3:

float x = 1 + 2;

When we combine operands (like 1 and 2) with an operator (like +), we call the whole collection an expression. All other common arithmetic is supported in expressions:

// subtraction

float a = 5.5 - 1.2;

// multiplication

float b = 5 * 2.4;

// division

float c = 4 / 2;

If there are multiple operators in a single expression, they are evaluated in order according to mathematical order of operations (in other words, multiplication and division are evaluated before addition and subtraction). You can use parentheses to group operations:

float d = (5 + 2) / (1 - 2.4);

There’s a subtle issue with the division operator (/). If we divide two integer values (i.e. not decimal values), then C++ will use integer division. Integer division always returns an integer, which is not what you usually expect. For example, if you write 1 / 2, you would expect this expression to evaluate to 0.5. However, because C++ is doing integer division, this will actually give us 0 — the fractional (decimal) part of the result is dropped.

If we want to perform floating point division, we need to turn one of our numbers into a float by adding a decimal:

// stores 0.5

float x = 1.0 / 2;

We could store the value in an int type variable as well, but beware: this will also drop the fractional portion of the result:

// stores 0

int x = 1.0 / 2;

Exercise 3: Expression practice

Instructor’s note: This is a painful exercise, but worth getting students to work through. It will help them avoid confusion down the road.

Evaluate the following expressions to figure out what is stored in each variable:

float x = 3 * 2 + -8 * 4 + 2 * 1.0;

float y = 1.5 * 4 + 2 / 1;

float z = 55 / 10 + (1.0 - 0.5) * 10;

int a = (2.0 / 10.0) + 100;

int b = a * 10;

float c = b / 10000;

Solutions

x = -24

y = 8

z = 10

a = 100

b = 1000

c = 0

Translations

Let’s revisit our example above, where we used a variable to reduce redundancy when drawing the same letter twice:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// A

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// A again

float offset = 300;

ofDrawLine(20 + offset, 200, 150 + offset, 20);

ofDrawLine(150 + offset, 20, 280 + offset, 200);

ofDrawLine(90 + offset, 100, 210 + offset, 100);

}

In programming, there is often more than one way to achieve something. In this example, we used a variable to save an offset along the x axis so we didn’t have to repeat ourselves by writing 300 in a bunch of places. Conceptually, what we’re doing is translating the letter to a different position — 300 pixels to the right of the original letter.

In this case, there’s an alternate way to achieve the same result: using ofTranslate(x, y):

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

ofTranslate(300, 0);

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

}

ofTranslate(300, 0) shifts the origin — or (0, 0) point — to the right 300 pixels. Then when we draw our letter with its upper left corner at (0, 0), it actually draws it at (300, 0). If we imagine openFrameworks as drawing to a canvas, ofTranslate is like moving the entire canvas. All drawing functions in openFrameworks are relative to the origin

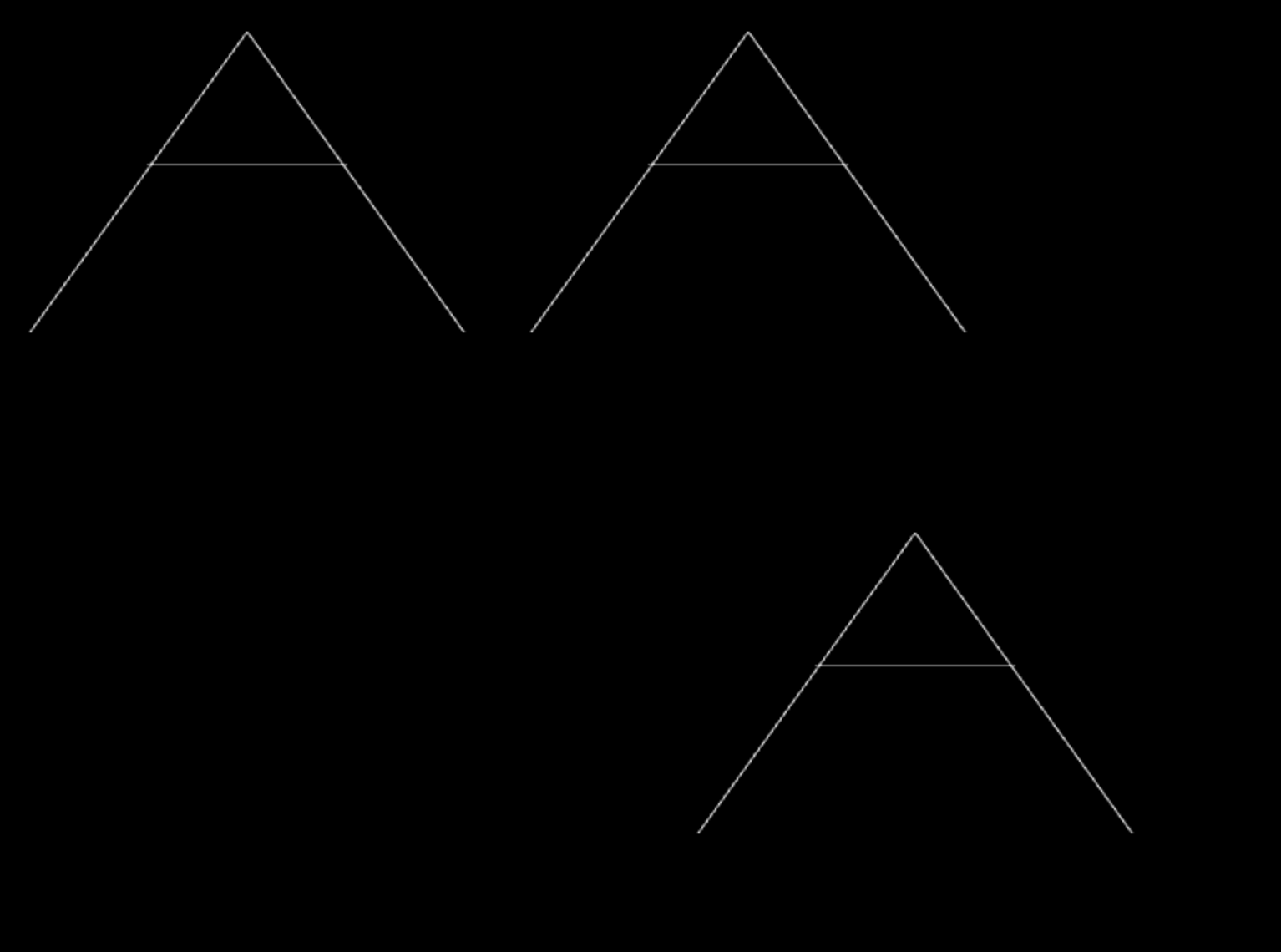

How is this approach different from using a variable? One core difference is that calls to ofTranslate accumulate. If we call ofTranslate twice, the second call is relative to the first. For example, if we draw three letters:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// move to the right by 300 pixels

ofTranslate(300, 0);

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// move to the right by ANOTHER 300 pixels

ofTranslate(200, 300);

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

}

This produces the following output:

The first call to ofTranslate moves the origin to (300, 0) and draws a letter there. The second call is applied on top of the that first transformation, and moves the origin to (500, 300) — 200 pixels to the right of and 300 pixels below (300, 0). The second letter is then drawn at (500, 300).

Writing our own functions

We’ve already been using two types of functions, discussed at the beginning of the day. Firstly, we’ve been putting code inside of the draw function that openFrameworks provides for us. Secondly, we’ve been calling functions that openFrameworks also provides for us. Now we’re going to extend our use of functions to writing and calling our own functions.

A function is a section of code that we can save and run at anytime. Just like variables store data, functions store code. One motivation for writing our own functions is reusability. In a similar way to how we used a variable to reduce redundancy, we can also use a function to reduce redundancy.

In our code for drawing a letter three times, you might have noticed that we’re starting to repeat ourselves — there are three identical lines of code occurring more than once. This is a clue that we might want to factor this code out into a function.

First, we need to declare this new function in our ofApp.h file:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void drawA();

// other functions not shown

}

Next, we need to define the function back in our ofApp.cpp file. This function definitions can go anywhere:

void ofApp::drawA() {

}

Next, let’s cut and paste the code to draw the letter and paste it into this new function:

void ofApp::drawA() {

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

}

After we finish defining our function, we need to call it. If we don’t call it, then the code inside of them is never executed. Let’s call our new function from within draw:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

drawA();

ofTranslate(300, 0);

drawA();

ofTranslate(200, 300);

drawA();

}

If we run this program, we see identical output to before. But our draw function is no longer cluttered with ofDrawLines. As we write larger programs, you might find it convenient to organize code in this way: putting sections of code into functions, and then calling on those functions from draw. Functions are essentially little “mini programs” which can be composed into the larger, main program.

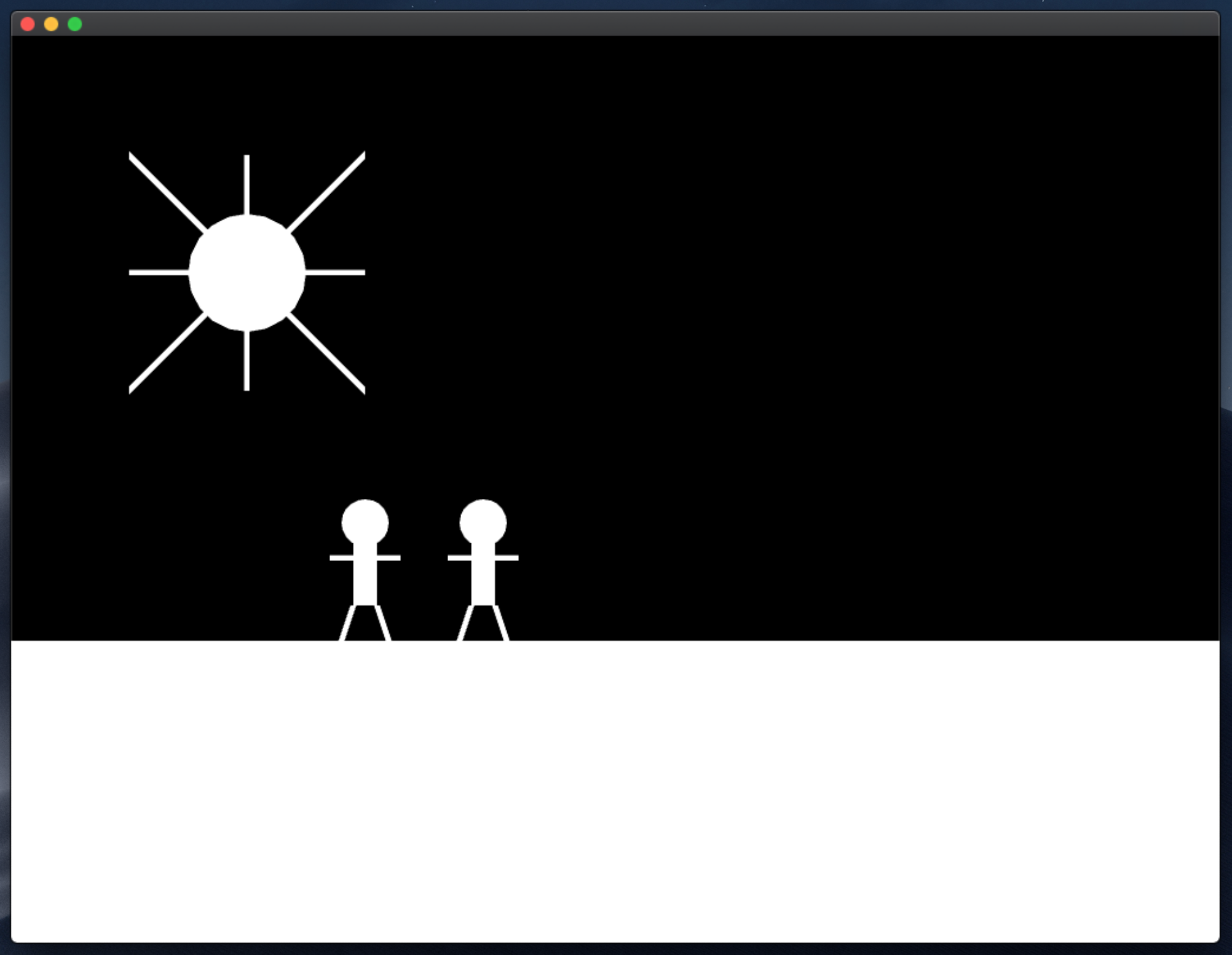

Homework 1: Draw a scene

Draw a scene using ofDrawLine, ofDrawRectangle, ofDrawCircle, and ofTranslate. At least one element in your scene must be repeated. Put the code for drawing this element into a function that is called multiple times from draw. You can use ofTranslate in combination with your custom function to move the element around the screen.

Solution

Here is the code for the example above:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

// draw ground

ofDrawRectangle(0, ofGetWidth() / 2, ofGetWidth(), ofGetHeight());

// draw sun

ofDrawCircle(200, 200, 50);

ofSetLineWidth(5);

ofDrawLine(100, 200, 300, 200);

ofDrawLine(200, 100, 200, 300);

ofDrawLine(100, 100, 300, 300);

ofDrawLine(100, 300, 300, 100);

// draw person 1

ofTranslate(300, ofGetWidth() / 2);

drawPerson();

// draw person 2

ofTranslate(100, 0);

drawPerson();

}

void ofApp::drawPerson() {

// origin of the person is the bottom of the figure

// therefore, a lot of these numbers are negative in order to draw

// shapes above the origin

// body

ofDrawRectangle(-10, -100, 20, 100 - 30);

// legs

ofDrawLine(-10, -30, -20, 0);

ofDrawLine(10, -30, 20, 0);

// arms

ofDrawLine(-30, -70, 30, -70);

// head

ofDrawCircle(0, -100, 20);

}

Common misconceptions & questions

-

Does the order of lines matter?

Most of the time, yes. Lines of code inside of a function are run sequentially, one right after the other. However, sometimes the order of code doesn’t matter. For example, when you’re defining a new function, it doesn’t matter where you put the function.

-

I’m confused by all the numbers in code like

ofDrawRectangle(20, 30, 60, 40)!This list of numbers tells

ofDrawRectangleexactly what sort of rectangle you want to draw. The order of the numbers is very important. The first two numbers are the (x, y) position of the top-left corner of the rectangle (in the above example, (20, 30)), and the second two numbers are the width and height (in this example, a width of 60 and a height of 40). Every function interprets the numbers you pass into it in a specific way.ofDrawRectangleis different fromofDrawCircle, for example. If you forget which order the numbers go in, you can refer to the openFrameworks documentation. (These numbers are technically called arguments, although students don’t often refer to them as such at this point.) -

How does the coordinate system of the window work?

The top left corner of the window is the origin, or point (0, 0). As you move to the right, you increase the x-coordinate. So point (100, 0) is 100 pixels to the right of the origin, but still at the top of the window. As you move downwards, you increase the y-coordinate. So (0, 100) is 100 pixels below the origin, but against the left-hand side of the window. Note that the y-axis is flipped relative to the standard x/y coordinates you may be familiar with from math class.

-

Can I change the width and height of the window?

Yes, you can do this by changing the following line in

main.cpp:ofSetupOpenGL(1024,768,OF_WINDOW);Change

1024to whatever width you want, and768to whatever height you want. -

I get an error that says “Expected ‘;’ after expression”

Almost every line in C++ ends with a semi-colon. This is an important piece of coding syntax.