BeginningCodersBootcamp

TODO: are we calling out

ofPoint p; p.x = 10; p.y = 20;

ofPoint p(10, 20);

Day 2: Random numbers, control flow and returns

- Lecture time: 3 hours

- Homework time: 2 hours

Learning outcomes

- Use

coutto log values - Use

ofRandomto produce random numbers in various ranges - Draw shapes with different colors; understand how

ofSetColoruses painter’s algorithm - Put variables in

ofApp.hthat persist over the lifetime of the program - Use the openFrameworks

setupfunction to initialize variables - If statements

- For loops

- Nested for loops

- Use the

sinfunction for animation - Write functions that return values

- Understand state updates of the form

x = transform(x)

Lecture

Logging things to the console

First, let’s learn how to log things to the console. This is useful for printing out the values of functions and variables.

void ofApp::draw() {

cout << ofGetWidth() << endl;

}

The << here is a special C++ syntax that allows us to send output to the console. We can chain together multiple parts of output using <<. In the above example, we’re printing out the width of the window, and then appending an endl. The endl stands for “end line”, and adds a line break to the output (the same as when you hit “return” on your keyboard).

Strings

If we want to log text to the console, then we can use strings. Strings are data type (like int, float, and bool) that stores text data. We won’t be using them much in this bootcamp, but it is useful to know how to print text to the console:

void ofApp::draw() {

cout << "Hello, world!" << endl;

}

This will repeatedly print Hello, world! to the console. If we want to print multiple values on the same line, we can string them together with the << operator:

void ofApp::draw() {

cout << "Hello " << "Alex" << endl;

}

We can also print a mix of text and numbers:

void ofApp::draw() {

cout << "The width of the program is " << ofGetWidth() << endl;

}

In creative coding, it’s often useful to print things to the console when you’re debugging, especially to get the value of variables in your program.

ofRandom

One tool we use a lot in creative coding is randomness. openFrameworks has an ofRandom function that generates random floating point (decimal) number for us. If we pass a single parameter into ofRandom, then we’ll get a random number between 0 and the passed value:

void ofApp::draw() {

// prints a random number between 0 and 100

cout << ofRandom(100) << endl;

}

If you run this program, you’ll see lots of numbers printed to the console — ofRandom gives us a different random number every time it is run. One thing to note is that the generated number will never include the upper bound, 100 (in other words, it is an exclusive upper bound).

Next we’re going to save a random value in a variable, and use it to draw something.

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// generate a random number between 0 and the width

float xPos = ofRandom(ofGetWidth());

// generate a random number between 0 and the height

float yPos = ofRandom(ofGetHeight());

// draw a circle at that random position

ofDrawCircle(xPos, yPos, 10);

}

Running this program causes a circle to flicker around the screen. Every frame, a new random position is chosen.

Let’s touch on a small syntax detail. If we want, we don’t need to save the ofRandom values to variables — we can insert them directly into the call to ofDrawCircle:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// draw a circle at that random position

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

}

This code has an identical effect to the previous version, but is more succinct. There is not really a preference for either style; one is more verbose, but potentially more clear. The other is shorter but potentially harder to understand.

There is another way to call ofRandom, by passing in both a min and max value:

void ofApp::draw(){

float x = ofRandom(300, 500);

ofDrawCircle(x, 100, 20, 20);

}

The circle will have an x position between 300 – 500 pixels.

TODO: exercise with randomness

For loops

Next we’ll learn about another control structure called loops. To motivate this, let’s say we wanted to draw a ton of circles every frame:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

}

This does what we want, but it’s redundant, and programmers hate redundancy. We’re repeating ourselves too much. In this case, we can use a for loop to automate this repetition.

void ofApp::draw() {

// run ofDrawCircle 10 times

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i = i + 1) {

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

}

}

For loops are very syntax heavy. What’s important to understand is that the code inside of the for loop will run 10 times. We can adjust the number of times the for loop runs by changing the loop bound:

void ofApp::draw() {

// run ofDrawCircle 100 times

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i = i + 1) {

ofDrawCircle(ofRandom(ofGetWidth()), ofRandom(ofGetHeight()), 10);

}

}

A more sophisticated example of looping is to use the looping variable i. The first thing to understand is that we can decide how we increment i. Let’s look at a few examples:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i = i + 1) {

cout << i << endl;

}

This prints out:

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

We can adjust the loop increment by adding 2 to i rather than 1:

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i = i + 2) {

cout << i << endl;

}

This prints out:

0

2

4

6

8

Now let’s use this i value in order to draw a series of circles:

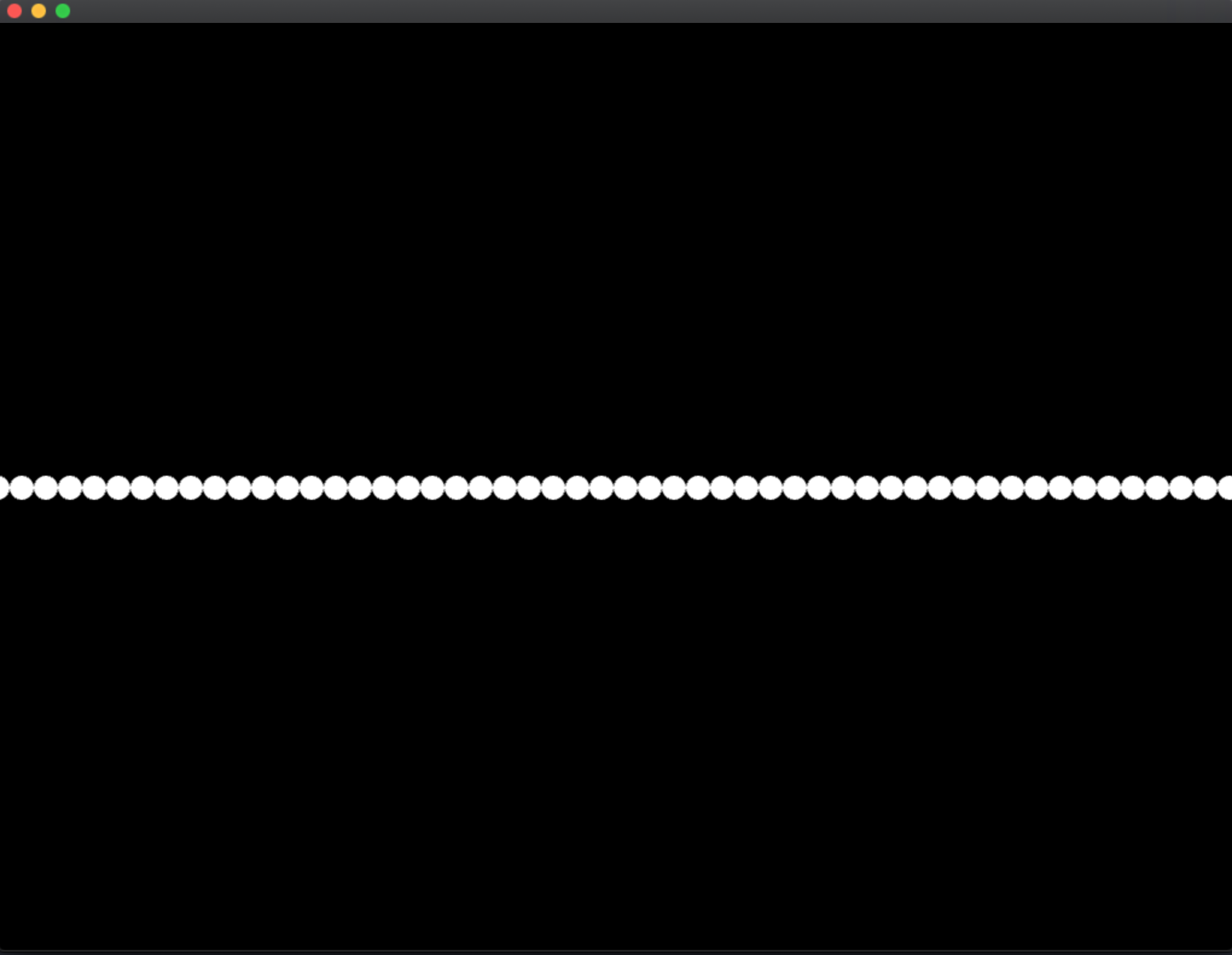

void ofApp::draw() {

for (int i = 0; i < ofGetWidth(); i = i + 20) {

ofDrawCircle(i, ofGetHeight() * 0.5, 10);

}

}

Syntax of a for loop

Let’s review the specific pieces of the for loop syntax:

for (initialization; condition; update) {

// body

}

- initialization: runs once at the beginning of the for loop and sets up the looping variable.

- condition: determines when the loop stops running. If the expression here evaluates to true, then the loop continues to run.

- update: updates the looping variable by some increment

- body: the code that runs every time the condition is true

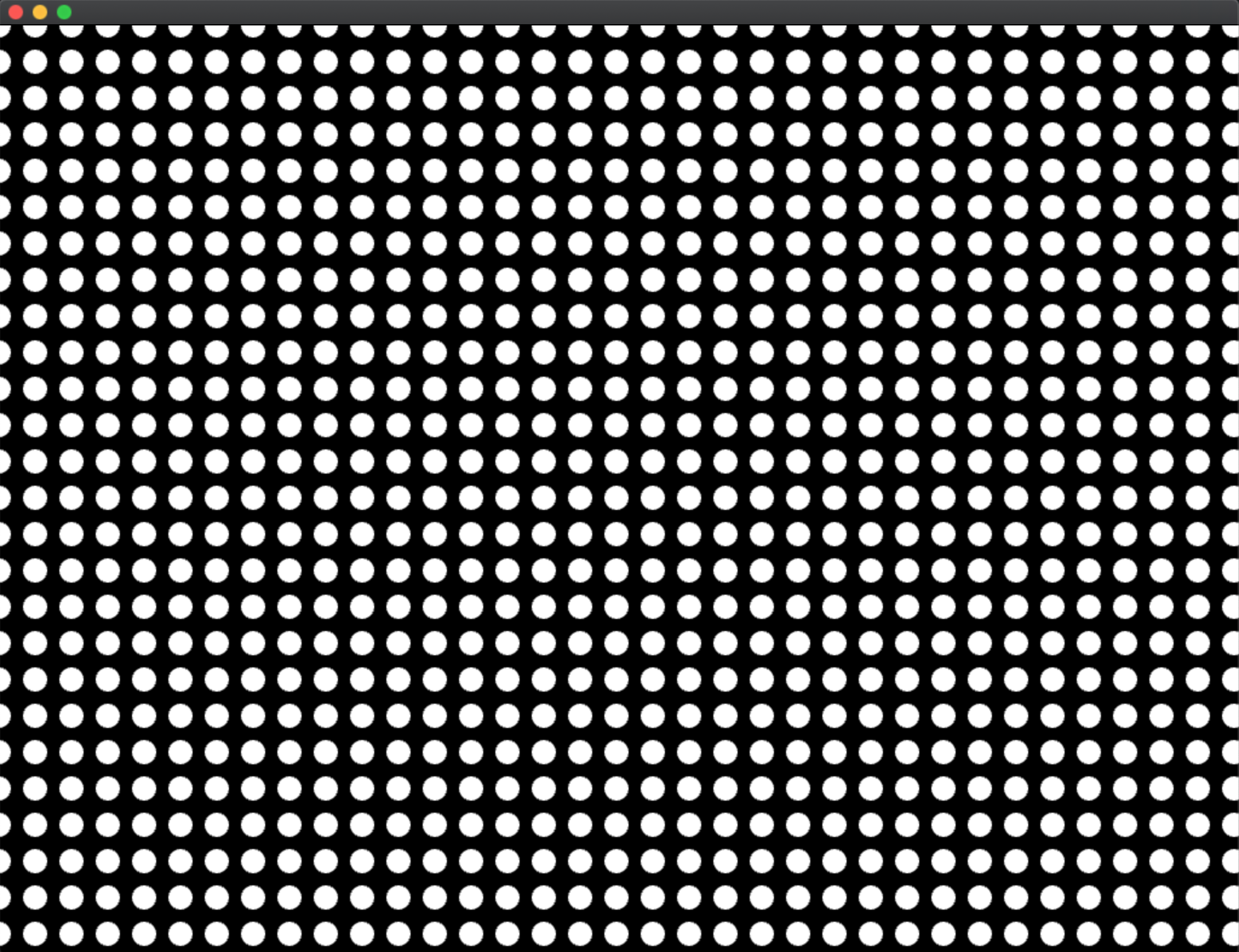

Nested for loops

We can put for loops inside of for loops. A common use case of this structure in creative coding is to draw grids. In the following example, we have one for loop that runs over the height, and inside of that, we have another loop that runs over the width. We draw circles using the looping variables i and j.

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

for (int j = 0; j < ofGetHeight(); j = j + 30) {

for (int i = 0; i < ofGetWidth(); i = i + 30) {

ofDrawCircle(i, j, 10);

}

}

}

This code produces the following image:

Exercise 1:

TODO: create lead up example to this w nested for loops TODO: rewrite below as exercise

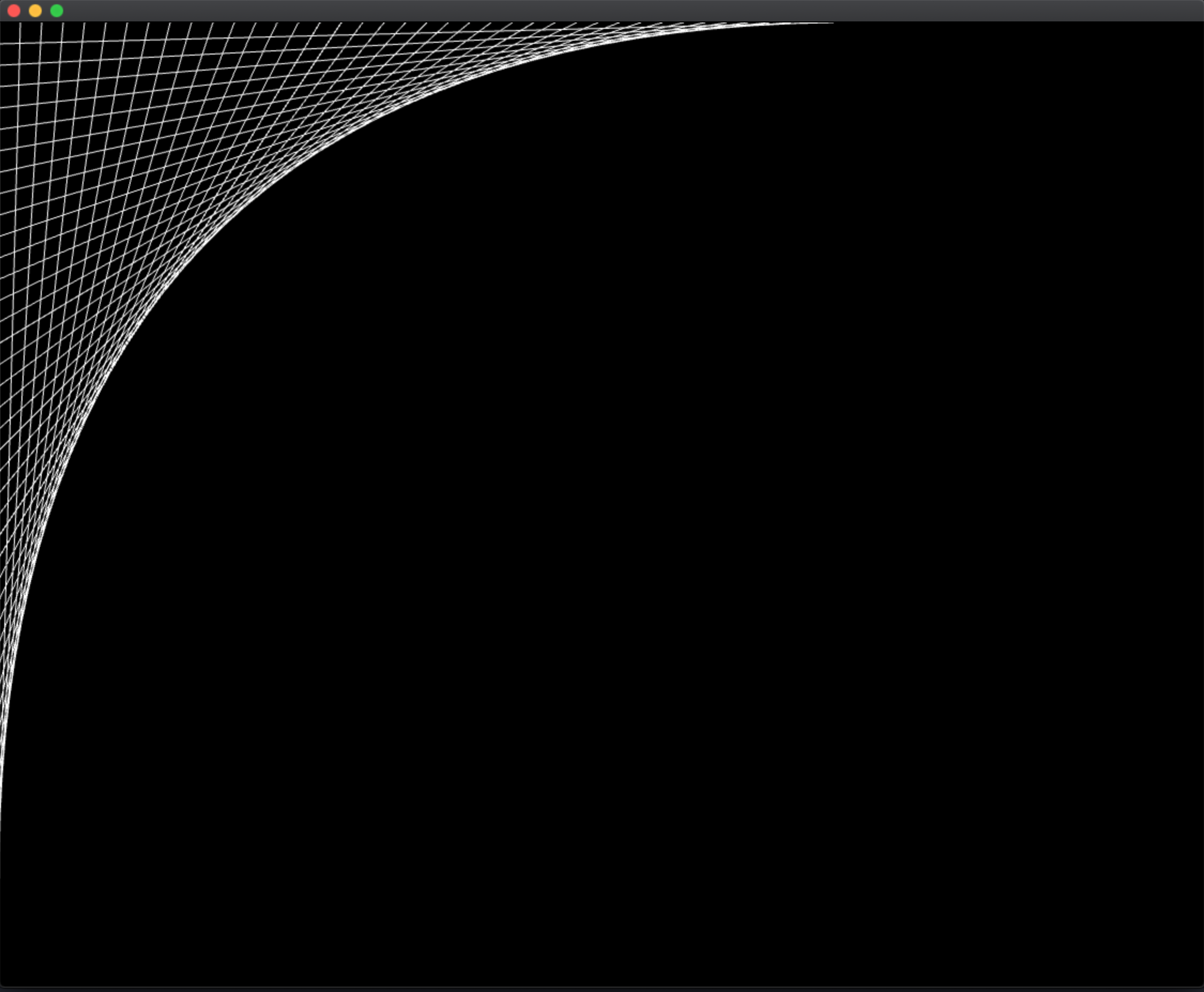

You might have drawn this pattern when you were bored in class as a kid.

How could we produce it with code? Because we’re drawing many lines, we know we’re going to use a for loop. Let’s say we want to draw this picture with 100 lines.

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

// what goes here?

}

}

There’s a pattern to where the lines start and end which might be easier to work out on paper or whiteboard. The first thing you need to emphasize is that we need to count forward and backwards at the same time. So let’s add a backwards counter inside of our loop:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

int backwards = 100 - 1 - i;

}

}

Why do we have the - 1 above? We want our backwards counter to start at 99, because our forwards counter i ends at 99. If you’re confused about why i ends at 99, think carefully about the bounds of the loop (i < 100).

Now let’s draw the lines:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

// i counts forwards, but we also need a counter

// that goes backwards

int backwards = 100 - 1 - i;

float x1 = ofGetWidth() / 100 * i;

float y1 = 0;

float x2 = 0;

float y2 = ofGetHeight() / 100 * backwards;

ofDrawLine(x1, y1, x2, y2);

}

}

This produces the picture that we want. It’s doing a lot of tricky math, so again it might be helpful to simulate the steps here and draw lines on the white board.

One final touch: we can factor out the 100 into a variable so we don’t have to keep repeating ourselves:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

int numSegments = 100;

for (int i = 0; i < numSegments; i++) {

// i counts forwards, but we also need a counter

// that goes backwards

int backwards = numSegments - 1 - i;

float x1 = ofGetWidth() / numSegments * i;

float y1 = 0;

float x2 = 0;

float y2 = ofGetHeight() / numSegments * backwards;

ofDrawLine(x1, y1, x2, y2);

}

}

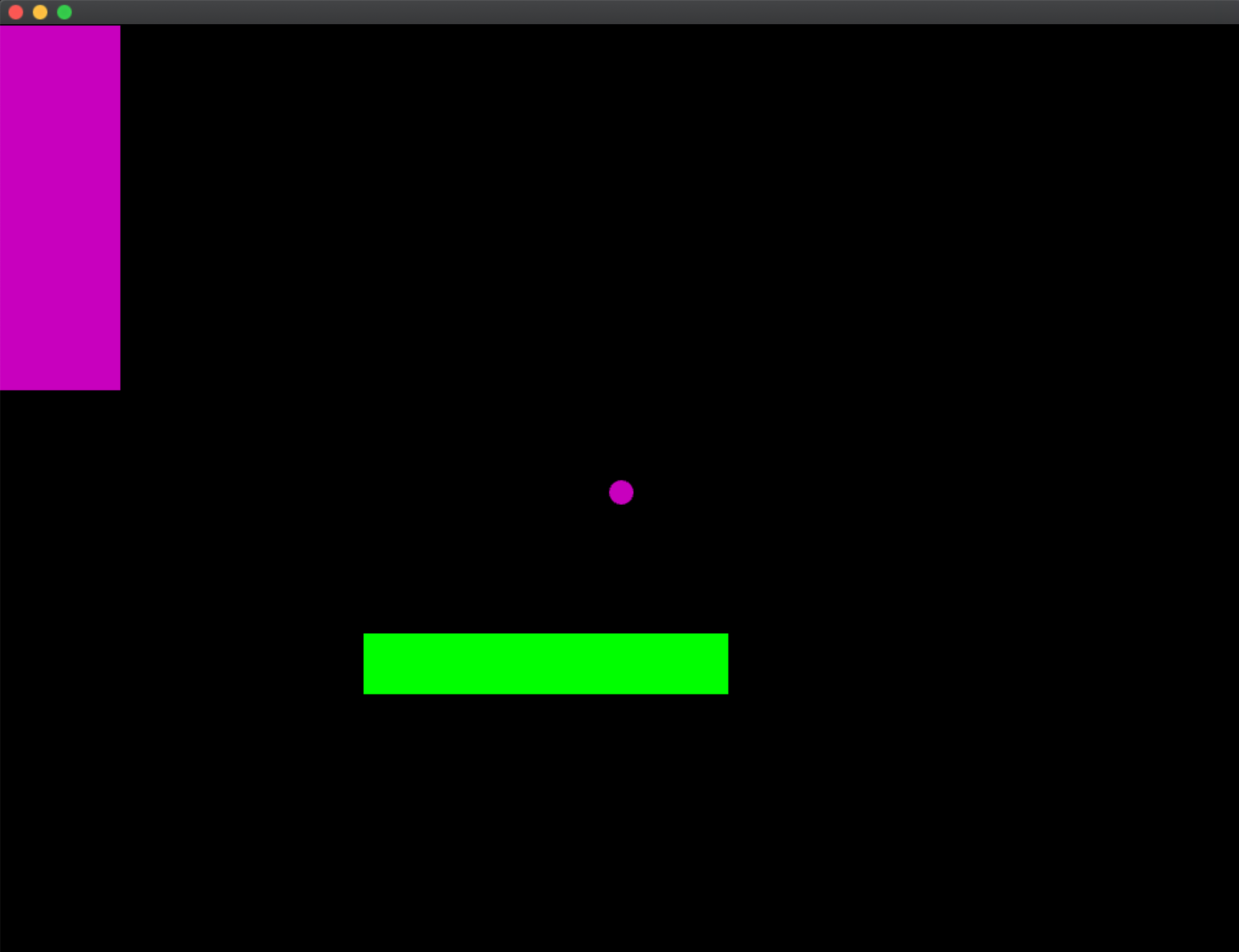

Color

We use the function ofSetColor(red, blue, green) to choose colors. Recalling the painter’s algorithm from day 1: openFrameworks models its graphics functions after a painter painting on a canvas. When we call ofSetColor, it’s analogous to a painter dipping their paintbrush in a bucket of paint. For example:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// put paint on the paint brush

ofSetColor(0, 70, 190);

// draw a circle at that random position, with the color

ofDrawCircle(0.5 * ofGetWidth(), 0.5 * ofGetHeight(), 10);

}

It’s important to understand that the color stays on the paintbrush until we set a different color.

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// put paint on the paint brush

ofSetColor(0, 70, 190);

// draw a circle at that random position, with the color

ofDrawCircle(0.5 * ofGetWidth(), 0.5 * ofGetHeight(), 10);

// this rectangle will also use the same color

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 300);

}

This gets into a detail about openFrameworks: it maintains state behind the scene. It’s like a drawing machine with lots of buttons and switches and an internal state. When we call ofSetColor, we’re setting the state of this machine.

To draw a new shape with a different color, we can call ofSetColor again before drawing that new shape:

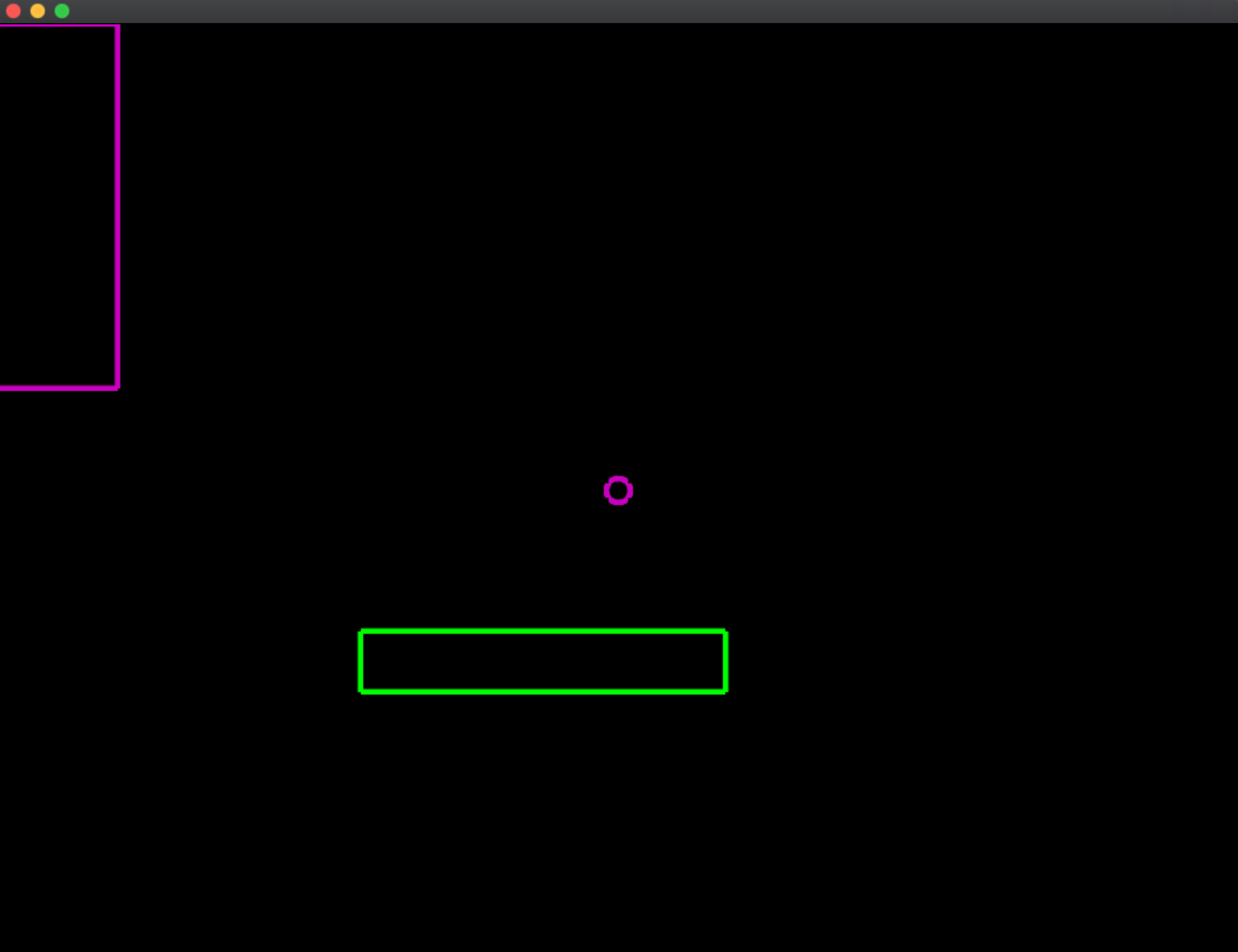

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// put paint on the paint brush

ofSetColor(200, 0, 190);

// draw a circle at that random position, with the color

ofDrawCircle(0.5 * ofGetWidth(), 0.5 * ofGetHeight(), 10);

// this rectangle will also use the same color

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 300);

// dip paintbrush in a new color of paint

ofSetColor(0, 255, 0);

ofDrawRectangle(300, 500, 300, 50);

}

There’s a function called ofNoFill() we can use to draw unfilled shapes. We can also use of ofSetLineWidth() to set the line size.

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

ofNoFill();

ofSetLineWidth(5);

// put paint on the paint brush

ofSetColor(200, 0, 190);

// draw a circle at that random position, with the color

ofDrawCircle(0.5 * ofGetWidth(), 0.5 * ofGetHeight(), 10);

// this rectangle will also use the same color

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 300);

// dip paintbrush in a new color of paint

ofSetColor(0, 255, 0);

ofDrawRectangle(300, 500, 300, 50);

}

Parameters

Recall from Day 1 that we created our own custom function that drew a letter (the example we gave was drawA). This function was a like a little mini program that we could run in our larger program. Let’s create some more mini programs.

We talked about how there are two motivations for functions: organization and reusability. Now let’s cover an example of how we might use functions for reusability.

Consider our example of drawing an “A” twice to the screen:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

// A

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

// A again

float offset = 300;

ofDrawLine(20 + offset, 200, 150 + offset, 20);

ofDrawLine(150 + offset, 20, 280 + offset, 200);

ofDrawLine(90 + offset, 100, 210 + offset, 100);

}

We discussed how to use a variable (offset) to reduce redundancy. But we might sense that there is still quite a bit of redundancy in this code. We have three lines of code that are almost the same repeated twice. If we find ourselves repeating code often, we should put this code inside of a function, so that we can reuse the code without repeating ourselves.

As before, let’s write a function drawA which is responsible for drawing an A character.

ofApp.h:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void drawA();

// other functions not shown

}

Now back in our ofApp.cpp file, we can call this function twice in draw:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

drawA();

drawA();

}

void ofApp::drawA() {

ofDrawLine(20, 200, 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(150, 20, 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(90, 100, 210, 100);

}

However, if you run this code, you’ll only see a single A. This is because our function is drawing the A twice in exactly the same location — we removed our offset variable that we were using to adjust the position of the second A. We need to be able to tell our function where it should draw the A. In order to do this, we’ll use parameters.

First, modify the ofApp.h file:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void drawA(int offset);

// other functions not shown

}

And then modify our function in the ofApp.cpp to use this offset parameter:

void ofApp::drawA(int offset) {

ofDrawLine(offset + 20, 200, offset + 150, 20);

ofDrawLine(offset + 150, 20, offset + 280, 200);

ofDrawLine(offset + 90, 100, offset + 210, 100);

}

As you can see, we’ve put a variable declaration for offset inside of the ( and ) of the drawA function. All parameter declarations go inside of these parentheses. You can use the variable inside of the function in the same way that you would use a normal variable that was declared inside of the function. However, parameters differ from normal variables in that they are initialized when the function is called.

For example, let’s add parameter values to where our function is called in draw:

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

drawA(0);

drawA(300);

}

When we call drawA(0) or drawA(300), we are initializing the value of offset inside of the drawA function to be 0 or 300, respectively. This allows us to reuse the same chunk of code, but adjust the value of a variable to change how the code is executed. Running this program should now produce two A’s, side by side. We’ve successfully reduced the redundancy of our original code.

Using the setup function

Thus far, we’ve only been putting code in the openFrameworks draw function. There are lots of other openFrameworks functions we can put code in. One such function is setup. Code placed setup only runs once, at the beginning of the program while code in draw runs many times a second. Example:

void ofApp::setup() {

cout << "hello from setup!" << endl;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

cout << "hello from draw!" << endl;

}

If you run this program, you’ll see output like the followng:

hello from setup!

hello from draw!

hello from draw!

hello from draw!

hello from draw!

hello from draw!

hello from draw!

...

As you can see, the setup line is printed just once at the beginning of the program, while the draw line is printed continuously afterwards. From now on, we’re going to begin putting code in either the setup function or draw function — or often both!

Using variables in the ofApp.h file

Let’s start with a simple program that draws a circle in the center of the window:

void ofApp::draw(){

float x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

float y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

We’re going to make a big change here. We’re going to move our x and y variables to the ofApp.h file. The full .h file should look like this:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void keyPressed(int key);

void keyReleased(int key);

void mouseMoved(int x, int y );

void mouseDragged(int x, int y, int button);

void mousePressed(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseReleased(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseEntered(int x, int y);

void mouseExited(int x, int y);

void windowResized(int w, int h);

void dragEvent(ofDragInfo dragInfo);

void gotMessage(ofMessage msg);

float x;

float y;

};

Now go back to your ofApp.cpp file and change the setup and draw functions to the following:

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

This will continue to draw a circle in the center of the screen, but now our variable is being declared in the .h file. But why would we want to do this? Well, now we can change the state of x over the duration of the program.

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

// add 1 to x

x = x + 1;

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

The line x = x + 1 is something we haven’t seen before. It’s important to understand that the right side of this assignment is evaluated: x + 1first. Then x is assigned to this new value. In other words, 1 is added to the variable x. If we run the program, we’ll see the x position of the circle change over time, because 1 is added to x on every frame of the program.

This is only possible because we have declared x in the .h file. Declaring it here causes x to persist over the lifetime of the program. This allows us to store state that persists.

Now we can do interesting things with this state:

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

x = x + ofRandom(-1, 1);

y = y + ofRandom(-1, 1);

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

This causes the circle to do a “random walk” across the screen. If we wait long enough, the circle will eventually leave the screen. If we want to keep the circle inside of the bounds of the screen, then we must use if statements.

Conditionals

Conditionals are a very powerful programming construct. They allow us to control the flow of the program based on conditions, and every programming language has them.

If we want to test to see if our circle is beyond the right hand side of the screen, we can write the following:

if (x > ofGetWidth()) {

// x is larger than the width!

}

This is called an “if statement”. We can put code within the { and } that we want to run if the case is true. For example, we can force the circle to stay within the bound:

if (x > ofGetWidth()) {

// if x is larger than the width, the reset x to be the width

x = ofGetWidth();

}

Exercise 1: Keep the circle within the bounds

Modify the random walk example so that the circle will stay within the bounds of the window. We’ve already written one if statement above to keep the circle from going off the right hand side of the window. Now we must write more if statements to prevent it from going off the other edges.

Exercise 1 solution

ofApp.h:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void keyPressed(int key);

void keyReleased(int key);

void mouseMoved(int x, int y );

void mouseDragged(int x, int y, int button);

void mousePressed(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseReleased(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseEntered(int x, int y);

void mouseExited(int x, int y);

void windowResized(int w, int h);

void dragEvent(ofDragInfo dragInfo);

void gotMessage(ofMessage msg);

float x;

float y;

};

ofApp.cpp:

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

x = x + ofRandom(-1, 1);

y = y + ofRandom(-1, 1);

if (x > ofGetWidth()) {

x = ofGetWidth();

}

if (y > ofGetHeight()) {

y = ofGetHeight();

}

if (x < 0) {

x = 0;

}

if (y < 0) {

y = 0;

}

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

// other functions not shown

Booleans

Conditionals and booleans are closely related. When we use an if statement, we put a boolean expression between the parentheses of the if statement:

if (<boolean expression>) {

...

}

In the same way that a mathematical expression in C++ evaluates to a number (for example, 3 + 5 evaluates to 8), a boolean expression evaluates to true or false. And in the same way that we can use operators like + and - in expressions, we can use operators in boolean expressions. We’ve already seen the use of greater than (>) and less than (<), which are arithmetic tests we can use to create a boolean expression. Here is a table of other arithmetic tests:

| operator | meaning | example |

|---|---|---|

< |

less than | 2 < 4 is true |

> |

greater than | 2 > 4 is false |

<= |

less than or equal to | 4 <= 4 is true |

>= |

greater than or equal to | 4 >= 4 is true |

== |

equal to | 2 == 4 is false |

!= |

not equal to | 2 != 4 is true |

There are also ways to combine these tests into more sophisticated expressions using boolean operators. For example, if we want to test if a variable x is greater than 10 and less than 20, we would write that as:

if (x > 10 && x < 20) {

// ...

}

The && here means “and”. Here is a table of some other boolean operators:

| operator | meaning | example |

|---|---|---|

&& |

and | 2 < 4 && 2 > 4 is true |

\|\| |

or | 2 < 4 \|\| 2 > 4 is false |

! |

not | !(2 < 4) is false |

We can also store boolean values in variables, just like int and float. These variables are of type bool:

bool myBoolean = false;

bool anotherBoolean = true;

bool largerBoolean = (5 < 2) && (4 > 2) || ((10 * 2) > 3);

// boolean variables can also be used in conditionals:

if (largerBoolean) {

// ... do stuff ...

}

As we’ve emphasized, if the expression in your if statement evaluates to true, then the code within the curly braces is executed. However, you might also want to run different code if the expression evaluates to false. You can do this by adding an else clause to the end of the if clause:

if (<condition>) {

// do some stuff if condition is true

} else {

// do some stuff if condition is false

}

Here’s another example with some actual code:

if (ofRandom(1) < 0.5) {

// 50% of the time, draw a rectangle

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 100);

} else {

// The other 50% of the time, draw a circle

ofDrawCircle(50, 50, 100, 100);

}

Exercise 2: Booleans and mouse position

Create a square that changes color when you move the mouse over it. This will involve using the openFrameworks variables mouseX and mouseY. You’ll also need to use a conditional to test if the mouse position is within the bounds of the square. In order to practice boolean expressions, you are only allowed to use a single if/else statement in your program.

Solution

void ofApp::draw(){

ofBackground(0);

float squareSize = 100;

float left = ofGetWidth() / 2 - squareSize / 2;

float right = ofGetWidth() / 2 + squareSize / 2;

float top = ofGetHeight() / 2 - squareSize / 2;

float bottom = ofGetHeight() / 2 + squareSize / 2;

if (mouseX > left && mouseX < right && mouseY > top && mouseY < bottom) {

ofSetColor(255, 0, 0);

} else {

ofSetColor(0, 0, 255);

}

ofDrawRectangle(

ofGetWidth() / 2 - squareSize / 2,

ofGetHeight() / 2 - squareSize / 2,

squareSize,

squareSize);

}

// TODO: add while loops!!!! // TODO: add lots more for loop stuff!!!

Homework 2: Bouncing circle (2 hours)

This homework is inspired by this gag from The Office. Create a program which contains a circle that bounces on the sides of the screen. A good starting point for this homework is the random walk circle that we created earlier. As a reminder, here is the full code for that example:

ofApp.h:

#pragma once

#include "ofMain.h"

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void keyPressed(int key);

void keyReleased(int key);

void mouseMoved(int x, int y );

void mouseDragged(int x, int y, int button);

void mousePressed(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseReleased(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseEntered(int x, int y);

void mouseExited(int x, int y);

void windowResized(int w, int h);

void dragEvent(ofDragInfo dragInfo);

void gotMessage(ofMessage msg);

float x;

float y;

float vx;

float vy;

};

ofApp.cpp:

#include "ofApp.h"

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

x = x + ofRandom(-1, 1);

y = y + ofRandom(-1, 1);

if (x > ofGetWidth()) {

x = ofGetWidth();

}

if (y > ofGetHeight()) {

y = ofGetHeight();

}

if (x < 0) {

x = 0;

}

if (y < 0) {

y = 0;

}

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

// other functions not shown

Hint: this problem will require you to add more variables to the ofApp.h file.

Homework 2 solution

ofApp.h:

#pragma once

#include "ofMain.h"

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

void keyPressed(int key);

void keyReleased(int key);

void mouseMoved(int x, int y );

void mouseDragged(int x, int y, int button);

void mousePressed(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseReleased(int x, int y, int button);

void mouseEntered(int x, int y);

void mouseExited(int x, int y);

void windowResized(int w, int h);

void dragEvent(ofDragInfo dragInfo);

void gotMessage(ofMessage msg);

float x;

float y;

float vx;

float vy;

};

ofApp.cpp:

#include "ofApp.h"

void ofApp::setup() {

x = ofGetWidth() / 2;

y = ofGetHeight() / 2;

vx = 1;

vy = 1;

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

x = x + vx;

y = y + vy;

if (x > ofGetWidth()) {

x = ofGetWidth();

vx *= -1;

}

if (y > ofGetHeight()) {

y = ofGetHeight();

vy *= -1;

}

if (x < 0) {

x = 0;

vx *= -1;

}

if (y < 0) {

y = 0;

vy *= -1;

}

ofDrawCircle(x, y, 10);

}

// other functions not shown

Vocabulary

Common misconceptions & questions

-

How does returning values work?

The important thing to understand about

returnis it allows one function to send an output to another function. Here’s a good way to think about it. Let’s say we have a function calledreturnsFivethat returns the number 5:float ofApp::returnsFive() { return 5; }Now let’s call this function in our draw function:

void ofApp::draw() { float myValue = returnsFive(); }What is the value stored in

myValue? The first thing the program does is evaluate the code on the right-hand side of the equals sign. In this case, that code is a call toreturnsFive. The program goes inside that function, runs it, and finds the value returned by the function. In this case, the return value is 5. You can think of program as replacing the call toreturnsFivewith its corresponding return value:void ofApp::draw() { float myValue = 5; }So in this case, the value 5 is assigned to

myValue. This technique of mentally replacing a function call with its return value is useful for understanding how function “send back” return values into another function. -

Assigning to variables

This is often confusing for students:

x = x + 1;The confusion stems from the subtle order of operations for assignment. The fact that the right hand side of the

=is evaluated first, followed by assignment, is not obvious. It can help to step through it like this:float x = 5; x = x + 1; becomes x = 5 + 1; becomes x = 6; so at the end, x is assigned to 6. -

Why does changing the color cause the color of things to change at the top of

draw?Here’s an example that causes this question to arise:

void ofApp::draw(){ ofBackground(0); ofDrawLine(0, 0, ofGetWidth(), ofGetHeight()); // put paint on the paint brush ofSetColor(0, 70, 190); // draw a circle at that random position, with the color ofDrawCircle(0.5 * ofGetWidth(), 0.5 * ofGetHeight(), 10); }Both the line and the circle will have the same color in this case. Why is that? Because the call to

ofSetColorsets the state of openFrameworks, and this state persists across draws. In other words, at the end of the draw function, the draw function starts again, and the color carries over from the past draw function. -

Error: Function definition is now allowed here

This often means you’re missing closing curly braces. For example:

void ofApp::draw(){ for (int j = 0; j < ofGetHeight(); j = j + 30) { for (int i = 0; i < ofGetWidth(); i = i + 30) { ofDrawCircle(i, j, 10); } }This will cause errors because the outer for loop is missing a closing curly brace

}. Let’s add it back in:void ofApp::draw(){ for (int j = 0; j < ofGetHeight(); j = j + 30) { for (int i = 0; i < ofGetWidth(); i = i + 30) { ofDrawCircle(i, j, 10); } } }You can see how the indentation helps us keep track of where our for loops begin or end. Every for loop needs an opening

{and a closing}.