BeginningCodersBootcamp

Day 4: Polylines, classes and 3D graphics

- Lecture time: 3 hours

- Homework time: 2 hours

Learning outcomes

- Use Polylines to draw shapes

- How to share openFrameworks apps

- Using the openFrameworks

updatefunction - Basic intro to C++ classes (member variables, functions)

- Transformations

- Using pushMatrix / popMatrix to remember transformation state

- 3D graphics

- Basic Lighting in openFrameworks

Lecture (3 hours)

Polylines

At the end of Day 3’s lecture, we built a vector of ofPoints in order to create a trail behind the mouse. As the mouse moved, we appended ofPoints to the end of the vector. Then we looped through the vector and drew lines between the points. Recall that declaring the vector looked like this:

vector<ofPoint> points;

Storing a list of points turns out to be a common pattern in creative coding and graphics in general. openFrameworks provides a type that we can use to store lists of points called a polyline. We can replace our vector of points with a polyline:

ofPolyline polyline;

Under the hood, ofPolyline stores a vector of points. But it adds additional functionality that we’ll find useful. Let’s rewrite our example from yesterday using ofPolyline:

// TODO: add link to prev example

ofApp.h:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

ofPolyline poly;

};

ofApp.cpp:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

poly.addVertex(mouseX, mouseY);

poly.draw();

if (poly.size() > 100) {

poly.getVertices().erase(poly.getVertices().begin());

}

}

We no longer need a for loop to draw our lines — ofPolyline does that for us with a call to poly.draw(). Also note that if we want to access the underlying vector of points, we can call poly.getVertices(). This returns the vector, which we can manipulate just like any other vector.

An example of another benefit of using ofPolyline is the getSmoothed function:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

poly.addVertex(mouseX, mouseY);

poly.getSmoothed(10).draw();

if (poly.size() > 100) {

poly.getVertices().erase(poly.getVertices().begin());

}

}

You can adjust the smoothing amount passed into getSmoothed(...) to get different effects.

Update vs draw

Thus far, we’ve been putting all of our code in the draw and setup function. You might have noticed that openFrameworks generates an update function as well. This function is for anything that updates state. If we want to use openFrameworks in the “right way”, we should separate our code out into code that updates, and code that draws. It’s useful to split up code into these two functions to keep things organized. Here’s an example of how we could split up the code above:

ofApp.cpp:

void ofApp::update() {

poly.addVertex(mouseX, mouseY);

if (poly.size() > 100) {

poly.getVertices().erase(poly.getVertices().begin());

}

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

poly.draw();

}

One rule with using update vs draw is that you cannot put drawing code inside of update — it simply won’t draw. Another rule: if you want to share a variable between update and draw, it must be placed in the ofApp.h file.

Aside: sharing applications

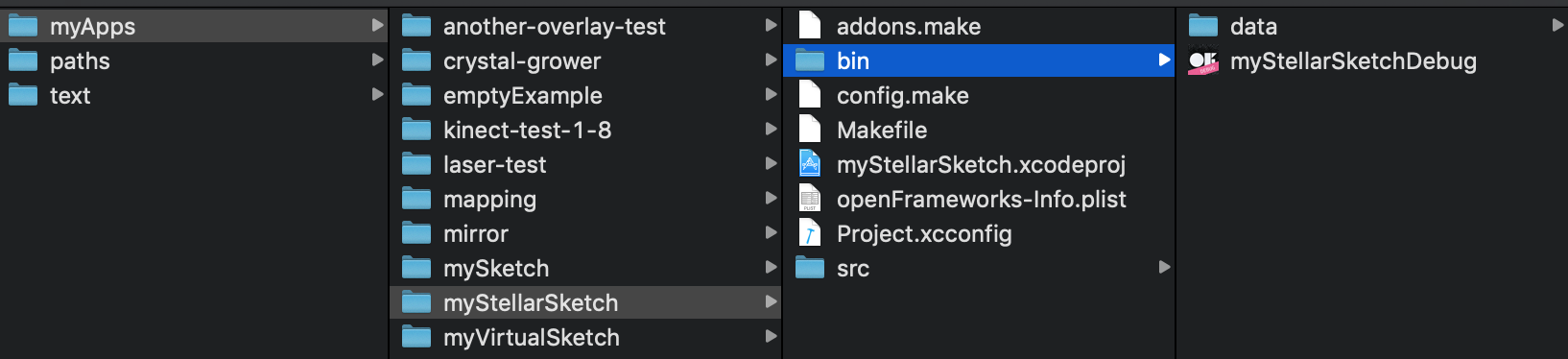

How would you go about sharing your openFrameworks creation with a friend? Find the folder in your operating system where your project was created. Every time you build and run your project within your IDE, an application is built and put inside of the bin folder of your project. Here’s what that looks like on MacOS:

In the above screenshot, the myStellarSketchDebug file is our application. You can double click on this file to launch your openFrameworks sketch. You could also email this file to a friend!

Bouncing balls

Let’s say we wanted to create a sketch with a bouncing ball. It might look similar to this:

ofApp.h:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

ofPoint position;

ofPoint direction;

};

ofApp.cpp:

void ofApp::setup() {

position.x = ofRandom(ofGetWidth());

position.y = ofRandom(ofGetHeight());

direction.x = ofRandom(-10, 10);

direction.y = ofRandom(-10, 10);

}

void ofApp::update() {

position = position + direction;

// the line above is shorthand for:

// position.x = position.x + direction.x;

// position.y = position.y + direction.y;

// keep ball within the bounds of the screen

// left bound

if (position.x < 0) {

position.x = 0;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// top bound

if (position.y < 0) {

position.y = 0;

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

// right bound

if (position.x > ofGetWidth()) {

position.x = ofGetWidth();

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// bottom bound

if (position.y > ofGetHeight()) {

position.y = ofGetHeight();

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

// we're using a different version of ofDrawCircle here, where we can pass in

// an ofPoint. this is identical to using ofDrawCircle(position.x, position.y, 10);

ofDrawCircle(position, 10);

}

// other functions not shown

// TODO: add link to day 2 homework? The bound checking code might be a little confusing, although you might have done something similar to this in homework 2. Let’s take a closer look at the left bound:

if (position.x < 0) {

position.x = 0;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

First we test to see if the x position of the ball is off the left edge of the screen. If it is, we need to do two things: reset the position so that it’s directly on the edge. If we didn’t do this, the ball could get stuck off the edge of the window. Next, we need to flip the x direction so the ball bounces.

Next, let’s add a line to update that implements gravity:

position.y = position.y + 0.2;

This accelerates the ball down by 0.2 every frame! Now we have a bouncy ball that responds to gravity.

Now let’s give our ball a radius and color. Add these variables to the .h file:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

ofPoint position;

ofPoint direction;

float radius;

ofColor color;

};

Here we’re introducing a new openFrameworks type: ofColor. ofColor stores an red-green-blue color, in the same way that ofPoint stores a position. In our setup function, let’s initialize our color and radius:

void ofApp::setup() {

position.x = ofRandom(ofGetWidth());

position.y = ofRandom(ofGetHeight());

direction.x = ofRandom(-10, 10);

direction.y = ofRandom(-10, 10);

radius = ofRandom(10, 20);

color = ofColor(ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255));

}

Now let’s update our draw and update to use this color and radius:

void ofApp::update() {

position = position + direction;

// the line above is shorthand for:

// position.x = position.x + direction.x;

// position.y = position.y + direction.y;

// keep ball within the bounds of the screen

// left bound

if (position.x < radius) {

position.x = radius;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// top bound

if (position.y < radius) {

position.y = radius;

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

// right bound

if (position.x > ofGetWidth() - radius) {

position.x = ofGetWidth() - radius;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// bottom bound

if (position.y > ofGetHeight() - radius) {

position.y = ofGetHeight() - radius;

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

}

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

// we're using a different version of ofDrawCircle here, where we can pass in

// an ofPoint. this is identical to using ofDrawCircle(position.x, position.y, 10);

ofSetColor(color);

ofDrawCircle(position, radius);

}

// other functions not shown

Adding our radius into our bounds checking ensures that the circle stays completely outside the bounds of the windows (you might have noticed that previously, the circle “passed through” the wall half way before bouncing). We also use the color and radius variables in our draw function to draw the circle with a specific radius and color.

What if we want more than one ball? Say, 1000 balls? Yesterday, we learned about how vectors allow us to store a list of values. How would we use vectors to store information about multiple balls? Here’s one approach we might start with:

ofApp.h:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

vector<ofPoint> positions;

vector<ofPoint> directions;

vector<float> radius;

vector<ofColor> color;

};

Now we can have multiple positions, directions, radii and colors. The positions[0] would correspond to directions[0], positions[1] would correspond to directions[1], etc. This approach is called parallel arrays, and it would allow us to achieve our goal of having multiple balls.

However, there is a better approach: using classes.

Classes

Classes allow us to create new types of objects. We can make a class that stores all the relevant data to represent a ball: position, direction, radius and color. To define a class, add the following to the ofApp.h file:

class Ball {

ofPoint position;

ofPoint direction;

float radius;

ofColor color;

}

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown};

This packages up our related variables into a single container called Ball. We can also add functions to our class as well. These functions live “inside” of the class:

class Ball {

ofPoint position;

ofPoint direction;

float radius;

ofColor color;

public:

void setup();

void update();

void draw();

}

We’re following the openFrameworks paradigm here by adding three functions: setup, update, and draw. Note that we could add whatever functions we want, but it’s common in openFrameworks to write these functions. We’ve declared these functions, but we still need to define them. We can do this back in our ofApp.cpp file:

void Ball::setup() {

}

void Ball::update() {

}

void Ball::draw() {

}

We can now cut-and-paste anything relating to our ball into these functions:

void Ball::setup() {

position.x = ofRandom(ofGetWidth());

position.y = ofRandom(ofGetHeight());

direction.x = ofRandom(-10, 10);

direction.y = ofRandom(-10, 10);

radius = ofRandom(10, 20);

color = ofColor(ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255));

}

void Ball::update() {

position = position + direction;

direction.y = direction.y + 0.5;

// keep ball within the bounds of the screen

// left bound

if (position.x < radius) {

position.x = radius;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// top bound

if (position.y < radius) {

position.y = radius;

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

// right bound

if (position.x > ofGetWidth() - radius) {

position.x = ofGetWidth() - radius;

direction.x = -direction.x;

}

// bottom bound

if (position.y > ofGetHeight() - radius) {

position.y = ofGetHeight() - radius;

direction.y = -direction.y;

}

}

void Ball::draw() {

ofSetColor(color);

ofDrawCircle(position, radius);

}

This is a big conceptual leap. We’ve been using objects (like ofPoint and ofPolyline). These objects store data and provide functions for using and manipulating that data. But now we’re defining our own type of object. We’re defining the type of data that it stores, and the functions which use that data.

Next, let’s add a vector of Ball to our .h file:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

vector<Ball> balls;

};

Finally, let’s update our ofApp::setup, ofApp::update and ofApp::draw to use this vector of Balls:

void ofApp::setup() {

// Add 1000 balls to the vector

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

// create the ball object

Ball b;

// call the setup function of the ball

b.setup();

// add it to the vector

balls.push_back(b);

}

}

void ofApp::update() {

// loop through the vector of balls and update each ball

for (int i = 0; i < balls.size(); i++) {

balls[i].update();

}

}

void ofApp::draw() {

// loop through the vector of balls and draw each ball

for (int i = 0; i < balls.size(); i++) {

balls[i].draw();

}

}

If you run this, you should see a thousand balls bouncing around the window!

// TODO: add video

Next, we’re going to modify our Ball’s setup function to accept a parameter:

ofApp.h:

class Ball {

ofPoint position;

ofPoint direction;

float radius;

ofColor color;

public:

void setup(ofPoint pos);

void update();

void draw();

};

ofApp.cpp:

void Ball::setup(ofPoint pos) {

position = pos;

direction.x = ofRandom(-10, 10);

direction.y = ofRandom(-10, 10);

radius = ofRandom(10, 20);

color = ofColor(ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255), ofRandom(255));

}

Now when we create our balls inside of ofApp::setup, we can pass in a position to Ball::setup:

void ofApp::setup(){

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

Ball b;

// pass in a position into the ball's setup function

b.setup(ofPoint(ofGetWidth() / 2, ofGetHeight() / 2));

balls.push_back(b);

}

}

Exercise 1: Add setup parameters

Add radius and color parameters to Ball::setup. This will follow a similar pattern as when we added the position parameter above.

Exercise 1 solution

// TODO:

Transformations

Now we’re going to introduce transformations. There are 3 transformation functions we’ll look at:

ofRotateDeg(degrees)ofScale(scale)

Next, let’s talk about ofScale:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofScale(2);

// move origin to 25, 50

ofTranslate(50, 25);

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 100);

// move origin right by 100 pixels

ofTranslate(200, 0);

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 100);

}

Our call to ofScale(2) here scales up the canvas by 2, zooming in by 200%.

Lastly, let’s talk about ofRotateDeg. This is the most useful transformation. Let’s say we want to rotate a rectangle. This is actually pretty hard to do if you think about it — it turns out that rotations involve some math. But we can use ofRotateDeg to do that fancy stuff for us.

The important thing to understand is that ofRotateDeg always rotates around the origin. Let’s see what we mean by that. We’ll rotate by mouseX so that we can see the rotation in action as we move the mouse back and forth:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofRotateDeg(mouseX);

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 100);

}

What you’ll notice now is that the rectangle is rotating by it’s upper left corner around the origin at (0, 0). Let’s say we want the rectangle to rotate around the center of the window. We know that ofRotateDeg always rotates around the origin, so we must move the origin to the center of the window:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofTranslate(ofGetWidth() / 2, ofGetHeight() / 2);

ofRotateDeg(mouseX);

ofDrawRectangle(0, 0, 100, 100);

}

This is a common pattern that you’ll often use for rotating objects. First, use ofTranslate to move the origin. Then, use ofRotateDeg to rotate around that point. What if we want the rectangle to rotate around its center? We can do this by drawing the rectangle centered around the origin, rather than on the top-left point:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofTranslate(ofGetWidth() / 2, ofGetHeight() / 2);

ofRotateDeg(mouseX);

ofDrawRectangle(-50, -50, 100, 100);

}

Drawing a rectangle with its top left corner at (-50, -50) and width and height of 100 means that the center of the rectangle will fall at (0, 0), which is the origin.

Push and pop

// TODO

3D graphics

So far, we’ve only used openFrameworks to draw 2D graphics. But there are functions in openFrameworks to draw 3 dimensional shapes. One simple example is drawing a box:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

ofDrawBox(200);

}

This draws a cube with a width of 200 pixels. We haven’t told the box where to be drawn, but by default, it will be drawn at the origin (0, 0).

When we’re drawing in 3D, we often want to introduce a camera to the scene that we can use to view our 3D shapes. openFrameworks has a built in camera that we can use. Add this to the .h file:

class ofApp : public ofBaseApp{

public:

// functions not shown

ofEasyCam camera;

};

Now to use the camera in your draw function:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

camera.begin();

ofDrawBox(200);

camera.end();

}

camera.begin turns on the “camera mode”. In this new camera mode, the origin is transformed to the center of the screen automatically. In addition, you can use your mouse to rotate around the origin. In order to see the 3D effect better, let’s add 3D axis:

void ofApp::draw() {

ofBackground(0);

camera.begin();

ofDrawBox(200);

ofDrawAxis(300);

camera.end();

}

// TODO: talk about why depth test is necessary

// TODO: add a light

Homework 3: 3D Scene

Create a grassy green plane with a box sitting on top of the plane. This will require using both ofEasyCam and transformations.

Solution

Vocabulary

Common misconceptions & questions

TODO

- What does

Ball bmean? - What does

b.setupmean? - What’s the difference between a class and an object?

- Can I still call openFrameworks functions inside of my class?

- Push without pop